I have only just discovered the amazing storyteller and author Octavia Butler. I’m writing this blog to ensure that you don’t miss out on the Parable of the Sower and Parable of Talents. The latter won the Nebula Award for Best Novel (1999).

Despite the Parable series being published in the 1990s, the books did not come to my attention until just this year. One reason for a revival of interest in Butler’s books is that her novel predicted the recent political campaign—Make America Great Again. In Butler’s series, the campaign is presented to an extremely destitute and dystopian country, under threat of further devastation as the very few corporations set up walled cities to recruit and protect workers, who in turn relinquish their freedom. Butler’s story begins in an enclave where lives a thirteen-year-old daughter of a Baptist minister. Hers is an independent, self-sustaining community that is largely enclosed and somewhat protected from the dangers of the outside world, but it is very fragile.

Lauren Oya Olamina feels that the real world is not reflected in the Christian religion still preached by her father. Hence, she founds a new religion that represents her world. The Parables novels are as much about the growth and maturity of Olamina’s religion as it is about her own growth and maturity. The futuristic religion is called Earthseed, and it is based on the premise that God is Change. Olamina describes God as both shaped by human perception and shaping humanity. Her message is revolutionary and simplistic:

Why is the universe?

To shape God.

Why is God?

To shape the universe.

Olamina loses her family in a criminal fire and barely escapes with her life to walk North. Along the way, she gains company, fellow travelers, and she spreads Earthseed as her mission.

One of the character conflicts for Olamina is her desire to be in a loving relationship with a companion and her desire to marry and have children with her personal and internally motivated mission to share Earthseed and invite others to believe with her. In the first book, Sower, we read Olamina’s personal introspection on the matter. She questions her own motivations. She challenges others to choose Earthseed, and holds her own emotions hostage to care for the foundling religion. In the sequel, Talents, the reader gets a glimpse of how Olamina’s passion affected those closest to her, namely, her husband, and her estranged daughter. We also get to see how her religion is received by her half brother who becomes a fairly prominent Christian pastor as America is rebuilding.

One thing that I found really interesting in Butler’s approach to dystopian fiction is that she not only writes of the experience in dystopia, but she writes from a perspective that looks back from a future beyond the initial dystopia. So, for example, as we read the continuing story of Olamina in the second book, we simultaneously get excerpts from Olamina’s grown daughter, who is looking back on the history that shaped not only her mother but the then matured religion Earthseed.

In the end, Christianity seems to remain the default religious experience of the post-dystopian United States of America; however, Earthseed earned a status beyond that of ‘cult’ and may even have been responsible for helping humanity reach toward colonization of distant planets. I assume that Butler’s eventual trilogy would have taken the story off-world if she had lived to complete the third book in the series.

The religious aspects of this book are a fascinating study. Olamina’s teenaged logic is sound. We are Godseed, created, and placed on the earth. She imagines that Christianity has failed humanity as a religion and failed to represent the true nature of God. Earthseed is her answer. It is a kind of humanism that ultimately presses humanity to scatter itself and evolve as a race among the stars. She does not, however, abandon the concept of God. It is merely that Olamina sees only one thing as constant and never fading—change. God is Change. She is not wrong, but somehow, it does not sound quite right. By the end of the series, we get a picture of Olamina’s vision in small resilient communities that help one another by contributing what they have to share and sharing what others contribute. These communities embrace one another and encourage religious reflection and true understanding, but also welcome anyone who wants to contribute and take part without “belief.” It is an idealistic vision that is robust in Butler’s fiction.

I can’t get away from the theological concepts presented in the Parable series. God indeed shapes the university, that God shapes us. But, is it also true that we shape God? In a way, yes. Our perceptions and experiences shape how we see God. God is described in various ways in the Bible, but we read our experience into those descriptions and shape God. There is truth in that. Ask any two people who have been raised by extremely different fathers to read biblical narratives about God being a father. One will say God as Father is good and immediately recognize the love and care of God, even one who can be stern at times. Another will say God as Father is scary and will see only a feared and mistrusted God. They will hide from the potential for angry abuse. I have encountered these and a range of others from students as we read through the Hebrew Bible.

The ethical question is, “should we shape God?” And that is the question that was pervasive in my mind as I read Olamina’s diary entries and watched her grow up from a young teenaged girl, questioning the religion that her father preached and lived out fully week to week. I cannot answer, and if I settle on something, I promise to update this blogpost!. Meanwhile, I think that Butler raises a salient point that reflects the condition of humanity, that we shape God with our experience, thoughts, and beliefs. We shape at least the concept of God in this way. Yet, God shapes the universe. It is a series of truths in contention. And maybe that is actually the best we can do when trying to understand God.

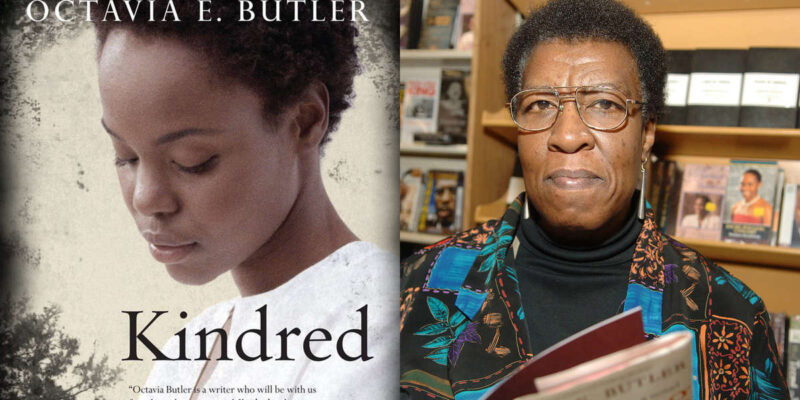

Coming up next, a response to Octavia Butler’s Kindred, both novel and graphic novel. Read the books. Please tell me what you think.

Dr. Erica Mongé-Greer, holding a PhD in Divinity from the University of Aberdeen, is a distinguished researcher and educator specializing in Biblical Ethics, Mythopoeia, and Resistance Theory. Her work focuses on justice in ancient religious texts, notably reinterpreting Psalm 82’s ethics in the Hebrew Bible, with her findings currently under peer review.

In addition to her academic research, Dr. Mongé-Greer is an experienced University instructor, having taught various biblical studies courses. Her teaching philosophy integrates theoretical discussions with practical insights, promoting an inclusive and dynamic learning environment.

Her ongoing projects include a book on religious themes in the series Battlestar Galactica and further research in biblical ethics, showcasing her dedication to interdisciplinary studies that blend religion with contemporary issues.