A reminder that this reading of Leviticus was part of a Bible study with a small group of friends, all women who needed an outlet during the COVID-19 pandemic. We have five Master’s degrees in topics ranging from Linguistics to Law to Chemistry, two doctorate degrees, and one doctoral candidate. If you missed it, catch up by reading Part I and Part II as well.

Only the Perfect Allowed

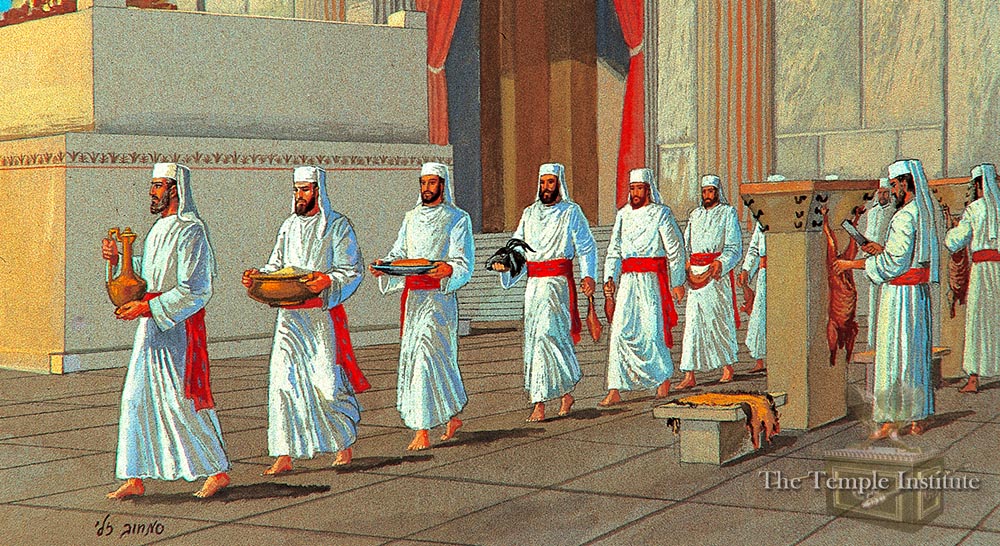

Looking more specifically at Lev. 21-24, we were very disturbed by 21.16 (and following) how the disabled could not work in the temple. It isn’t easy to imagine something like this in today’s world. We ended up talking about various ways that people try and justify strange or difficult passages in the Bible. A lack of understanding of the science behind physical development, for example. Or is it a cultural inclination to separate the perfect from the imperfect? It isn’t easy to understand how this makes sense in a text that is supposed to reach across time intentionally. But, it is a good reminder that no matter how much spiritual revelation is present, the authors of the biblical text were situated in a particular time and knew only certain things to be true. Unless we believe that the authors of the biblical text were encoding secret messages to 21st-century audiences, in which case, the message would have been confusing to an ancient audience; we must then believe in the integrity of the text. The authors wrote to communicate a truthful message to their own culture and the people who lived among them. This invites us to the difficult task of reading the biblical text, trying to determine what the authors were communicating to the audience before them, and then translating and interpreting that message in today’s modern world. Scholars call this process hermeneutics. At the very least, we may observe in this text that the ancient Israelites prioritized perfect specimens of animals and humans to participate in divine work, even though that meant excluding others.

Random Bits & Lots of Questions

Chapter 24 seemed like a montage of story bits and commands thrown together because they didn’t fit anywhere else. The commandment about blaspheming God caught our attention and seemed to deserve some reflection or at least discussion. The root of the word translated as blaspheme is q-l-l in Hebrew. Its meaning corresponds with “to ease, lighten, or a curse.” Well, which is it? Like with many of the regulations put forward in Leviticus, we do not get any definitive answers. But, we are left with a lot of questions. Three verses later, we learn that the punishment for death is death. In ancient Near Eastern law, these phrases are not absolute; they are more likely descriptive of what has been done in the past, rather than prescriptive as what is done. They function like guidelines. Just because a person commits murder does not mean they will die, but it at least means they deserve to die. The ambiguities surrounding the presentation of law in Leviticus lead me to suspect that ancient communities had just as much trouble sorting out what was the right thing as we do in today’s world.

In the following chapters, we find different rules for relatives versus for the stranger or foreigner. It is challenging to process the instructions about taking slaves from foreigners, especially in light of the constant warnings in Deuteronomy that the Israelites should not take slaves since they were once enslaved. There is a contradiction in these instructions. They have laws for taking slaves, but God does not seem to condone slavery. So how can we accept such writing as divinely inspired? (This is an ongoing question that I cannot answer at the moment.)

Chapter 26 revisits the Decalogue and reiterates God’s promise to bless (by means of fertility) and God’s punishment if the people are disobedient. This is a theme consistent in Deuteronomy and the book of Joshua. The reader or audience of this text must also choose. These passages follow the blessing/curse motifs of ancient Near Eastern treaties, and so implicate the reader to actively make a choice to enter into covenant with God or to forsake God’s commands. This description would have been very well understood by any ancient Near Eastern listener. Covenants are an important social component of life in the ancient world.

Reading Leviticus Broadly

If the opening chapters of Leviticus should be read along with a Butcher, then the last chapters should be read with the help of an Economic Strategist. The economic principles of releasing (slaves, land, and property) from ownership counter the capital investment strategies used today. In Leviticus, no person owns the land because it belongs to God. Is there a model of this today? Can government-subsidized housing be a potential application of such an idea? In our small group, we had so many questions about whether this was a more capitalistic strategy or a socialistic one. I think we finally resolved to determine that the Bible didn’t present those same categories. Once again, we are reminded to have some humility when reading these ancient texts.

I would love to listen in on a conversation between psalmists and the author of Leviticus. On the one hand, we have a barrage of legal code and instruction thrown at us in Leviticus. On the other hand, in the Psalms, we read very different accounts of God’s grace, God’s sympathy, and God’s willingness to be reminded of a covenant of faith over and over again. Surely, we are not meant to read Leviticus on its own. Without understanding other scriptures, Leviticus feels desperate and unrealistic. When reading other books, we find that the Israelites did not do a perfect job following their own instruction. How then were they able to find favor with God? Perhaps it is wise to place Leviticus in a larger context. As one of my study group reminded us, “the long arm of history argues toward justice.” Maybe the book of Leviticus is just trying to nudge the needle a tiny bit from harsher laws. This is a case where the gap of time and culture presents more obscurity than clarity for understanding the purpose of this text.

Growing up in church, the Bible was always presented as something incredibly unique and special, blessed by God, but, by the way, it condones slavery and prejudices against the disabled and women. This results in questions that cannot be ignored, like does the Bible affirm a terrible religion? How can the Bible be an infallible text? Perhaps the goal is not singular understanding. Rather, the biblical text is meant to be read in community, acknowledging failed relationships and difficult human journeys. Maybe the Bible brings these things up to force us to speak them and experience the pain and insecurities of our fellow humans.

If we read as a community, the Bible prompts us in several difficult-to-talk-about subjects. In a way, we are then encouraged to talk about such things openly, appealing not to judge one another but to understand. The Bible presents snapshots of people trying to follow God throughout time in various political and economic circumstances. Ultimately, we may even find encouragement in these difficult passages if we can find an honest attempt to follow God in complete and utter imperfection.

Dr. Erica Mongé-Greer, holding a PhD in Divinity from the University of Aberdeen, is a distinguished researcher and educator specializing in Biblical Ethics, Mythopoeia, and Resistance Theory. Her work focuses on justice in ancient religious texts, notably reinterpreting Psalm 82’s ethics in the Hebrew Bible, with her findings currently under peer review.

In addition to her academic research, Dr. Mongé-Greer is an experienced University instructor, having taught various biblical studies courses. Her teaching philosophy integrates theoretical discussions with practical insights, promoting an inclusive and dynamic learning environment.

Her ongoing projects include a book on religious themes in the series Battlestar Galactica and further research in biblical ethics, showcasing her dedication to interdisciplinary studies that blend religion with contemporary issues.