Read or Listen to this blogcast

I have just completed my recent reading of The Narnia Chronicles, and it has been quite a long time since I remembered the story C. S. Lewis wrote in The Last Battle. This finalé to the series is a remarkable commentary on modern theology that is simple presented as religion in Narnia, a story so accessible it is often recommended to children.

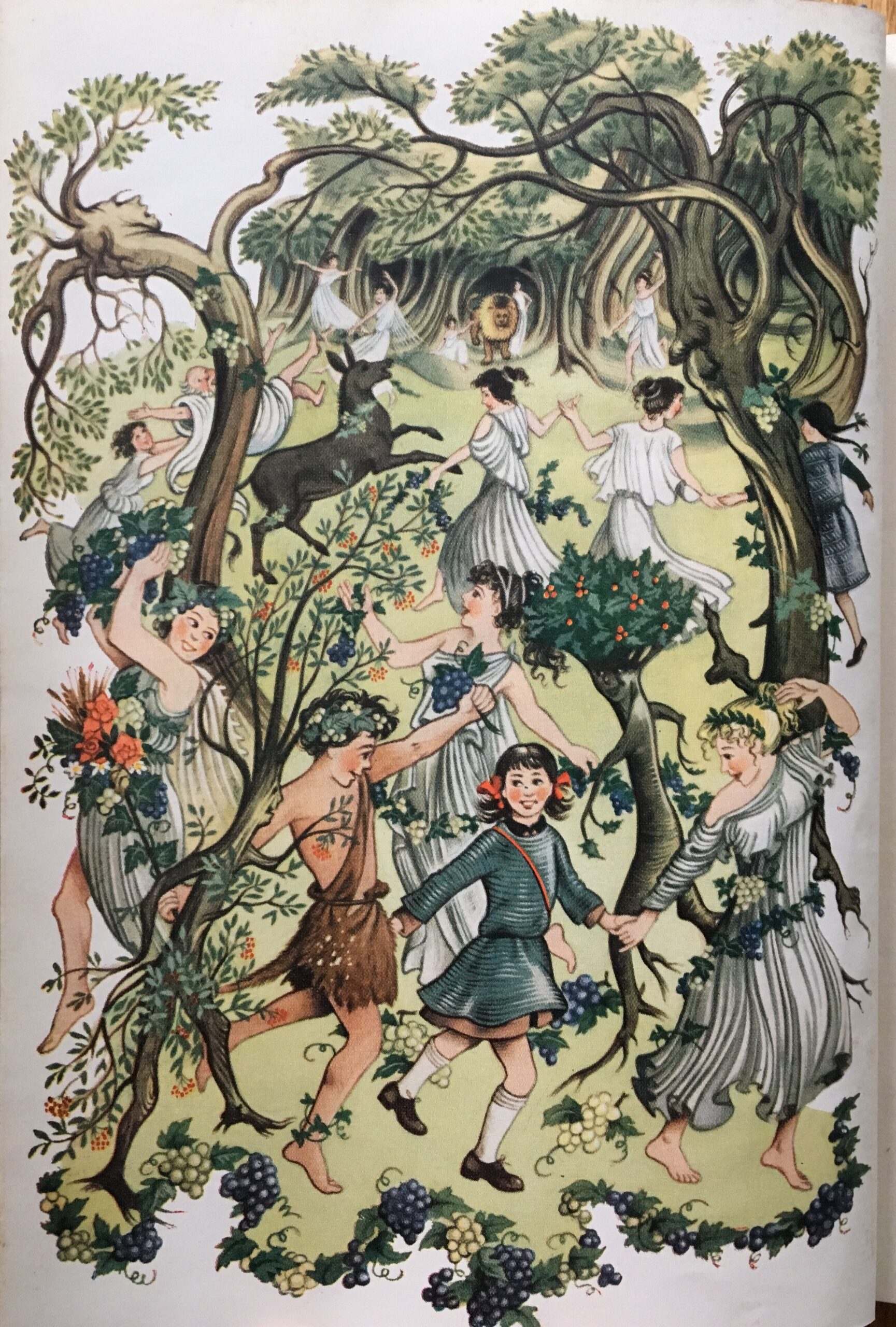

The Last Battle begins as a wilderness story, sounding a little bit like any Rudyard Kipling narrative. A shrewd Ape and a gullible Donkey happen to find an old discarded lion’s pelt. The Ape decides to dress his Donkey sidekick as a Lion and use the mirage to order about the Narnians, dwarfs, dryads, and animals in the name of the Great Lion Aslan. Unfortunately, the Ape’s mirage kingdom is soon allied with Narnia’s enemy, men from another region who worship a different God, called Tash. It is not long before the Ape has conned the masses, and he forms a new religion in Narnia to quiet the doubts and questions that arise quickly. This new religion has a new God, called Tashlan, and under this new regime, there is slavery, confusion, and ill-gotten alliances.

The Ape is both clever and ignorant. What results from the emergence of this mixed-bag religion is blind allegiance and dissent. The King of Narnia, assisted by two children from our world, who have been transported there to help him, tries to ally his people to fight in the name of Aslan, but many have had enough of gods they cannot see. It is the beginning of the end.

Narnian Theology

Two things stand out to me in this book. One is the portrayal of everlasting existence, which corresponds to what could be called an afterlife for the characters in the world of the Narnia Chronicles. The other is the formation of atheism which could be best described as a type of humanism, except that it appears to evolve in a non-human species—the dwarves.

First, the formation of a chimera deity, in this case, a combination of Aslan, the God of Narnia, and Tash, worshipped by the Calormen people. As the deception about Aslan’s presence became less likely to the forest’s denizens, the Calormen also grew cynical of their own deity, Tash. In response to the King’s attempt to expose the lying Ape, the dwarves turn against all religion in Narnia—”the dwarves are for the dwarves,” they chant. Aside from the few outliers, the dwarves adopt their own a-theism, denying the existence of any deity and relying only on themselves for protection.

The Afterlife is an important theological discussion in our world, but in the world of Narnia, it is a very subjective topic. Since many worlds exist in different time aspects of the same Universe (?), and life in another world does not preclude returning or traveling to yet another, the afterlife is a very loose concept. Regardless, it seems that the children, all the former (and evidently forever) royalty of Narnia, have died in their world of origin and therefore cannot return. Their “heaven” is a world where Aslan resides. I found it a fascinating theological point that C. S. Lewis included the Calorman Prince in the human party of Aslan’s world. Fascinating because the Prince was not a believer in Aslan. He accidentally wandered into this heavenly realm, where he discovers his love and fascination for a belief in a new religion that he was never exposed to in Tash’s human colony.

The Last Battle gives readers a final battle to end the sad state of affairs in Narnia and at the same time a glimpse of eternal joy for its characters. It is a satisfying conclusion to a book series that is filled with fantasy, adventure, and a dreamy world.

Read other blogs about The Chronicles of Narnia, or explore my comments on other fictional literature.

Dr. Erica Mongé-Greer, holding a PhD in Divinity from the University of Aberdeen, is a distinguished researcher and educator specializing in Biblical Ethics, Mythopoeia, and Resistance Theory. Her work focuses on justice in ancient religious texts, notably reinterpreting Psalm 82’s ethics in the Hebrew Bible, with her findings currently under peer review.

In addition to her academic research, Dr. Mongé-Greer is an experienced University instructor, having taught various biblical studies courses. Her teaching philosophy integrates theoretical discussions with practical insights, promoting an inclusive and dynamic learning environment.

Her ongoing projects include a book on religious themes in the series Battlestar Galactica and further research in biblical ethics, showcasing her dedication to interdisciplinary studies that blend religion with contemporary issues.