The Jewish holiday Purim bookmarked my year of celebrating major Jewish holidays, and it fell merely days before my family embarked on a significant cross-country move. So naturally, this meant a few last-minute store visits to purchase baking supplies and simplifying the menu to accommodate our temporary dining table surface. Nevertheless, we made more than enough food for dinner and snacked on stuffed pastries before, during, and after the meal.

I had always heard that Purim was the biggest gift-giving party holiday in the Jewish calendar (not Hanukkah, as many Christians assume due to its proximity to Christmas). And up to this point, that was pretty much the extent of my knowledge about the celebration of Purim. I knew that it featured a reading of the Hebrew Bible book of Esther and that people often dressed in costumes. We did not dress up in Esther-themed costumes, but we did participate in some decorative traditions. Our Days United box came with some animal ear costumes and instructions for making Hamentaschen. Thanks to some help from a friend, I quickly found a dairy-free adaptation, and we made Hamentaschen for the first time.

Purim Decor and Costumes from the Days United box. Purim Table setup

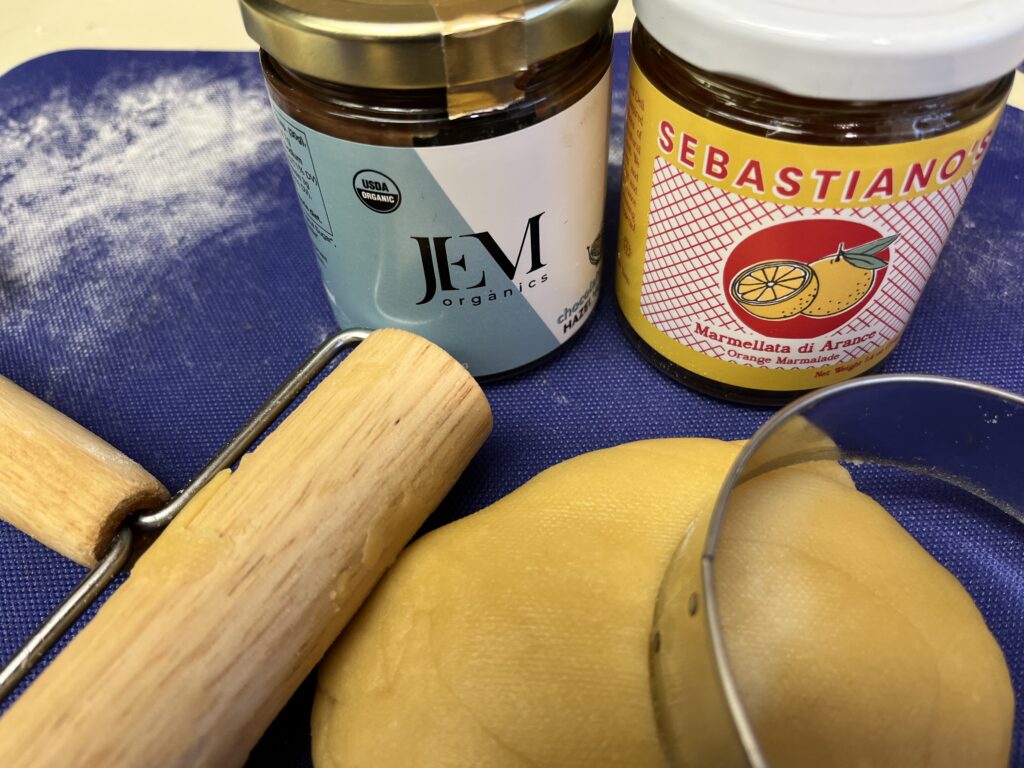

We bought Philo dough and made a mixture to wrap and bake vegetable samosas. As in other Jewish holiday meals, there is a food theme. Tastes and textures represent various features of the story or the religious focus in the celebration. We talked about how having similar textures, tastes, and smells every year would reinforce the memory through sensory experience. This year (2022), Purim fell on St. Patrick’s Day, so we incorporated the Irish holiday with Guinness instead of wine. We enjoyed a delicious meal of doughy, stuffed foods and a baked chicken vegetable dish.

Hamentaschen with Chocolate & Marmalade Purim Hamentaschen Purim St. Patty with Guiness Purim Costume Selfie Samosas for Purim

We read a version of the Esther story from our holiday box guidebook. Since Haman is the villain in the story, obsessed with plotting against Mordecai, his family, and more broadly, the Jewish community, whenever his name is mentioned, the party yells ‘boo’ and shakes a rattler. This made the story extra entertaining, and we had fun engaging in the group experience. After reading the standard version of the story, we read a ‘Mad Libs’ style version of Purim stories. All four of us took turns requesting parts of speech and reading the silly result aloud. I appreciated the holiday’s intentional efforts to bring together family to encourage all manner of sensory participation, seeing, hearing, touching, tasting, smelling … the holiday comes alive in the memory through regular practice and engagement with the senses.

One thing that stood out to me as a Hebrew Bible scholar is that the reading did not represent the entire book of Esther. The story ended with Mordecai and Esther saving the Jews and exacting the punishment of execution against Haman and his family. We did not read the rest of the book, where Mordecai and the Jews continue to slaughter thousands upon thousands of people in the name of righteous vengeance against the anti-Semitic mentality Haman brought to court. Some scholars believe this is a hyperbolic function of the narrative, meant to encourage a vulnerable ethnic population by punching up with slander and hyperbole. Other scholars believe this to be just retribution that aligns with early Israelite manifest destiny efforts. Any way you approach the narrative, there is a real problem of violence that is rarely addressed. This disturbed me, especially given that most of the Jewish holidays we have celebrated included an emphasis on social justice and awareness of diversity and inclusion. I do not have any conclusive thoughts about the violence in this story. But I advocate sitting with uncomfortable passages in the Bible and just letting it be. It is okay to feel uncomfortable and disquieted by such violent reactions. I think there is no better response.

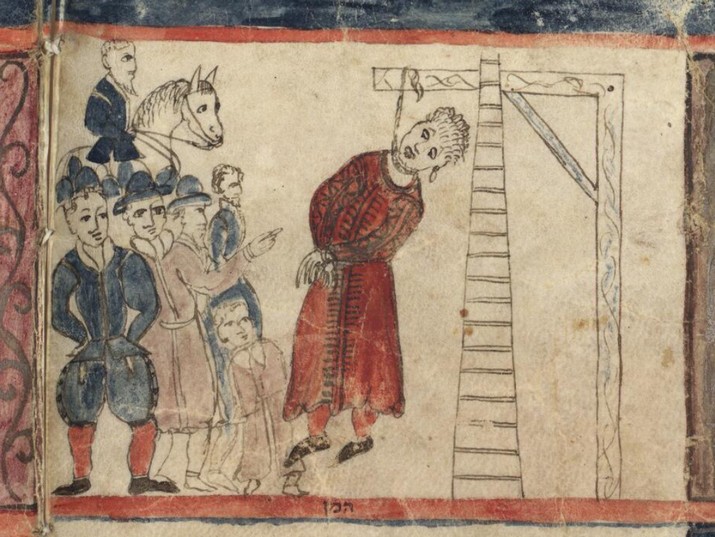

In the story of Esther, a dissident queen (Vashti) boldly stands against her master in the act of integrity and self-preservation. She is abruptly and violently discarded. Esther is put through a rigorous contest at the bequest of her uncle Mordecai. While not necessarily violent, it was disruptive. Esther gave up her own life to step into a marriage of convenience. Her family is threatened with violent execution by the evil Haman. The violence does not go away, but it is reversed, falling instead on Haman and his family. And then, violent executions continued and spread throughout the region. All Jews who had heard about Mordecai’s victory turned against those who hated them and slaughtered hundreds and thousands along Haman. And after that day, there was a day of rest and feasting, which became known as Purim. The holiday celebration was a proclamation signed by Queen Esther and is still practiced today, millennia later. The Esther story contains no mention of God, and so it may be illustrated without causing it to become unkosher. There are many illustrated Esther scrolls, and you can view the 400-year-old Esther Ferrara Scroll online.

The Esther Ferrara Scroll shows the coronation of Queen Esther. The Esther Ferrara Scroll offers the banquet of Queen Vashti The Esther Ferrara Scroll shows Haman’s execution by hanging as a warning against those who plot against the Jews, as told in Esther, Purim.

While we celebrated Purim nearly a month ago, I am only now posting due to my recent transition from the Pacific Northwest to the Bible Belt. I find myself primarily reflecting on the violence in Esther in light of Passover, which is today, also Good Friday, and Easter Sunday, which comes in two days. The connections between Passover and Easter are well known. The Last Supper was certainly a Passover feast, and the prophecies connecting the slaughtered lamb and Jesus, the lamb of God, are well attested in modern religious beliefs. How is Esther related to Passover? I recently learned that the story of Esther is contained within the Islamic Quran. In multiple places, Haman is mentioned as a cohort of Pharoah in that they both plot and act against the Israelites with the intent to destroy God’s chosen people. Pharaoh of Egypt is well known as an antagonist in the Hebrew Bible narrative, but Haman is less so. In light of the convergence of holidays this season, thinking about Purim in light of Passover, perhaps it is appropriate to consider this interfaith context. Haman is a type of Pharoah in the Esther story, plotting to destroy the Jews only to be defeated and overrun. But an even greater interfaith context expands to include also the convergent Christian narrative of Easter, which coincidentally shares its roots with the namesake Esther; both names share an etymology connection with Ishtar, the Babylonian goddess of fertility, representing rebirth and renewal.

Purim was the last of eight Jewish holidays we celebrated this past year. To read more about how we experienced these celebrations, check out my other blogposts on Jewish Holidays.

Dr. Erica Mongé-Greer, holding a PhD in Divinity from the University of Aberdeen, is a distinguished researcher and educator specializing in Biblical Ethics, Mythopoeia, and Resistance Theory. Her work focuses on justice in ancient religious texts, notably reinterpreting Psalm 82’s ethics in the Hebrew Bible, with her findings currently under peer review.

In addition to her academic research, Dr. Mongé-Greer is an experienced University instructor, having taught various biblical studies courses. Her teaching philosophy integrates theoretical discussions with practical insights, promoting an inclusive and dynamic learning environment.

Her ongoing projects include a book on religious themes in the series Battlestar Galactica and further research in biblical ethics, showcasing her dedication to interdisciplinary studies that blend religion with contemporary issues.