Steve Nolan’s book called Film, Lacan and the Subject of Religion (2009) is a book that looks at the relationship between film and religion. Nolan advocates for engaging with film as it is experienced or consumed as a means of religious interpretation. In this way, films may be interpreted by the visual equivalent of “reader response.” This is his interpretive approach. In addition, responses may consider religious influences in a film by considering theology, text, and anthropology categories.

Nolan introduces film and religion by describing how two buildings shaped his reality as a maturing youth. One was the dark and visually enhanced movie cinema, and the other was the large pristine and sacred church. His book explores the intersection of faith and film to encourage the reader to reflect on how their own faith is encountered by and in cinematic representation. he does this by incorporating psychoanalytic approaches to understand how people experience religion in film.

Cinematic Beginnings

Early cinema focused on retellings of the story of Christ. Cecille B. De Mille produced the most famous of these in the early 20th Century. Nolan raised the matter of a perceived conflict between the entertainment industry and the moral guardianship of the church. The Catholic Church responded to these concerns by creating the “Legion of Decency” (1934), which appealed to church members to avoid patronizing films that offended decency and Christian morality. The conflict between the Catholic church and the entertainment industry leads to a broader discussion about portraying the divine in visual film. Nolan’s description of the conflict leads to the question—can “God” or a divine entity be adequately represented in a cinematic image?

According to the New Testament, Christ represents the image (Gr. eikon) of the invisible God. (Colossians 1.15) Christ’s life, situated in a particular space and time in humanity’s history, is a precedent for displaying the divine image. At least, this is a way of responding in defense of historical portrayals of the divine Christ in film. When an historical event, like the life of Christ, is contemporized for a new generation, it is removed from the time-space of the original event. Nolan calls this a form of “actualization.” He cites one of my personal favorites, Brevard S. Childs in Memory and Tradition in Israel, who wrote in favor of speech as polysemic.

“Behind what a discourse says, there is what it means [veur dire], and behind what it means, there is against another intended meaning [vouloir-dire], and nothing will ever be exhausted by that—except that it comes down to this, that speech has a creative function, and that it brings into being the very thing, which is none other than the concept.”

Childs, Brevard S. Memory and Tradition in Israel, London: SCM Press, 1962, 242.

Childs wrote about the activity of keeping stories alive for the sake of remembrance. By remembering, future generations engage in participation. Nolan uses this concept to support religious imagery in cinematic imagery. The divine image may be brought forward in new tellings to remember and thereby encourage participation in the making (and critiquing) of religious ideals.

Film and Religion Together

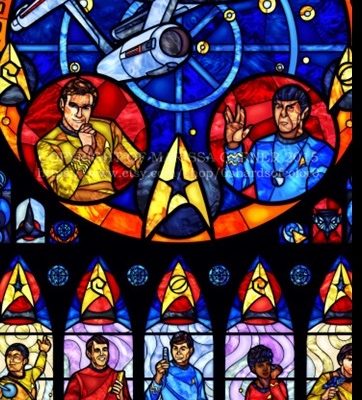

Since I am preparing to teach a course called Cinematic Religion this year, I am particularly interested in the intersection of film and religion. Not only do some films explicitly represent religious ideas, but religious ideas creep into films. Many cinematic expressions document and recreate religious endeavors in the name of exploring and preserving religious ideas, like The Apostle (1997), Little Buddha (1993), and The Passion of Christ (2004). Others use religion as a tool to explore humanity, like Battlestar Galactica (2004-2008), Lucifer (2016-2020), and many more. As I explore religious themes in these films and series, I notice that I learn more about humanity’s desire to shape religious expression than I do about true religion.

Dr. Erica Mongé-Greer, holding a PhD in Divinity from the University of Aberdeen, is a distinguished researcher and educator specializing in Biblical Ethics, Mythopoeia, and Resistance Theory. Her work focuses on justice in ancient religious texts, notably reinterpreting Psalm 82’s ethics in the Hebrew Bible, with her findings currently under peer review.

In addition to her academic research, Dr. Mongé-Greer is an experienced University instructor, having taught various biblical studies courses. Her teaching philosophy integrates theoretical discussions with practical insights, promoting an inclusive and dynamic learning environment.

Her ongoing projects include a book on religious themes in the series Battlestar Galactica and further research in biblical ethics, showcasing her dedication to interdisciplinary studies that blend religion with contemporary issues.