This week, the Ancient Near Eastern Languages in Connection eLecture series featured the research of two scholars on the connections between Aramaic and Arabic in the ancient Near East. Dr. Na’ama Pat-El is an Associate Professor of Semitic Philology at Harvard University. Dr. Phillip Stokes is an Assistant Professor in the Arabic program at the University of Tennessee.

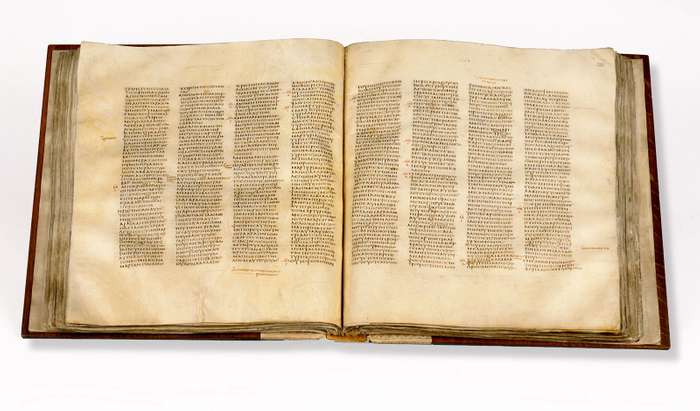

Scholars of late antiquity attest to a swift change from Aramaic to Arabic in spoken language. Arabic took over for Aramaic as a spoken language in Late Antiquity. It is unclear exactly how that transition took place, but it seems to most scholars that it happened fairly quickly. So quickly, in fact, that Aramaic remained a primary written language in several regions where Arabic was the primary spoken language. The presentation given demonstrated an attempt to interpret written records to discover how Aramaic may have influenced Arabic.

Substrate influence is the kind of shift in a language that occurs when one language is being learned by people who previously spoke a different language. This influence is identified in several categories to show that the source of change is not internal. Certain features must be present to show that the new language is being influenced by the old. The study presented in this eLecture looked at several variables that need to be in place for such a study. The focus was on identifying the substrate influence of Aramaic in early speakers of the Arabic language.

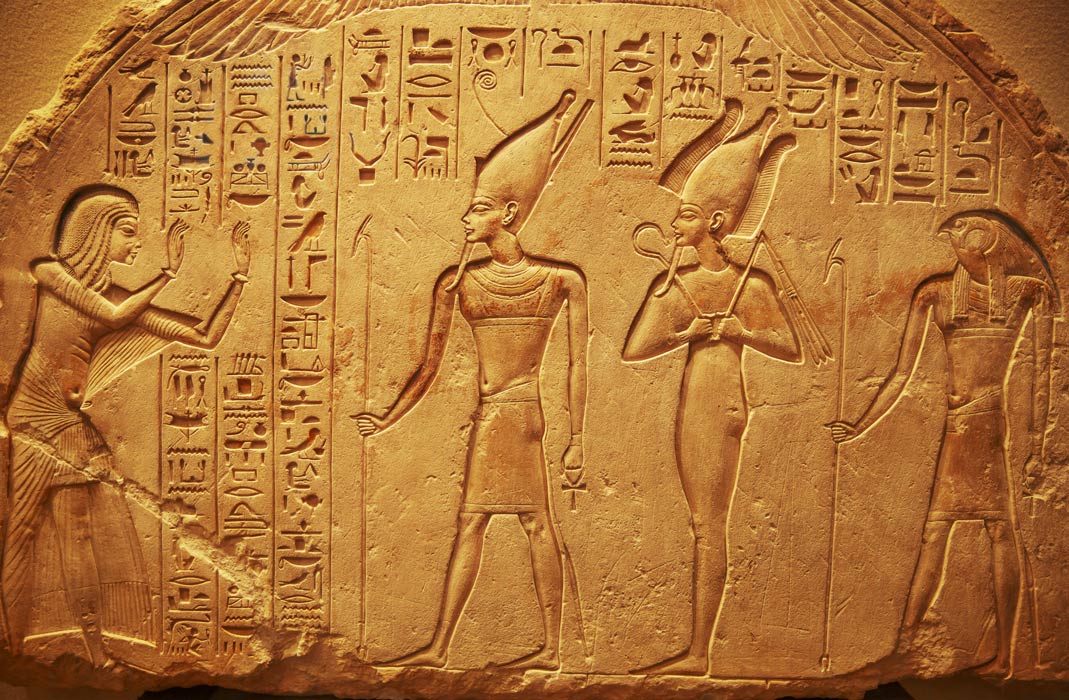

Arabic became a widely spoken language by the time of the Common Era. Late 8th century BCE Akkadian references include Arabic influences, demonstrating that Arabic had a far and fast reaching range of influence in Semitic language regions. There is also evidence of Arabic influences upon 5th century BCE Greek texts. For example, the goddess, al-ilat, identified with a definite article tied to Arabic language structure.

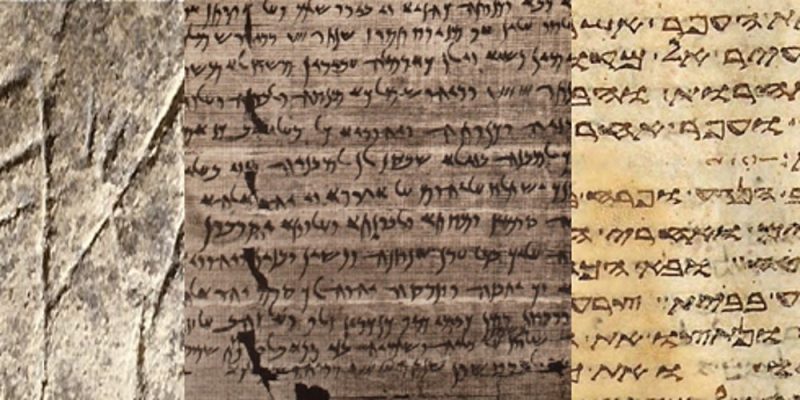

In the first millennium CE, there is a more recognizable influence. Several written texts suggested that Aramaic was the primary written language during the Christian era, although Arabicisms were scattered. This study asked questions about which direction the influence moved, from what language to what language. Since samples of spoken language are sparse, the primary evidence for identifying linguistic influence is ancient written textual sources.

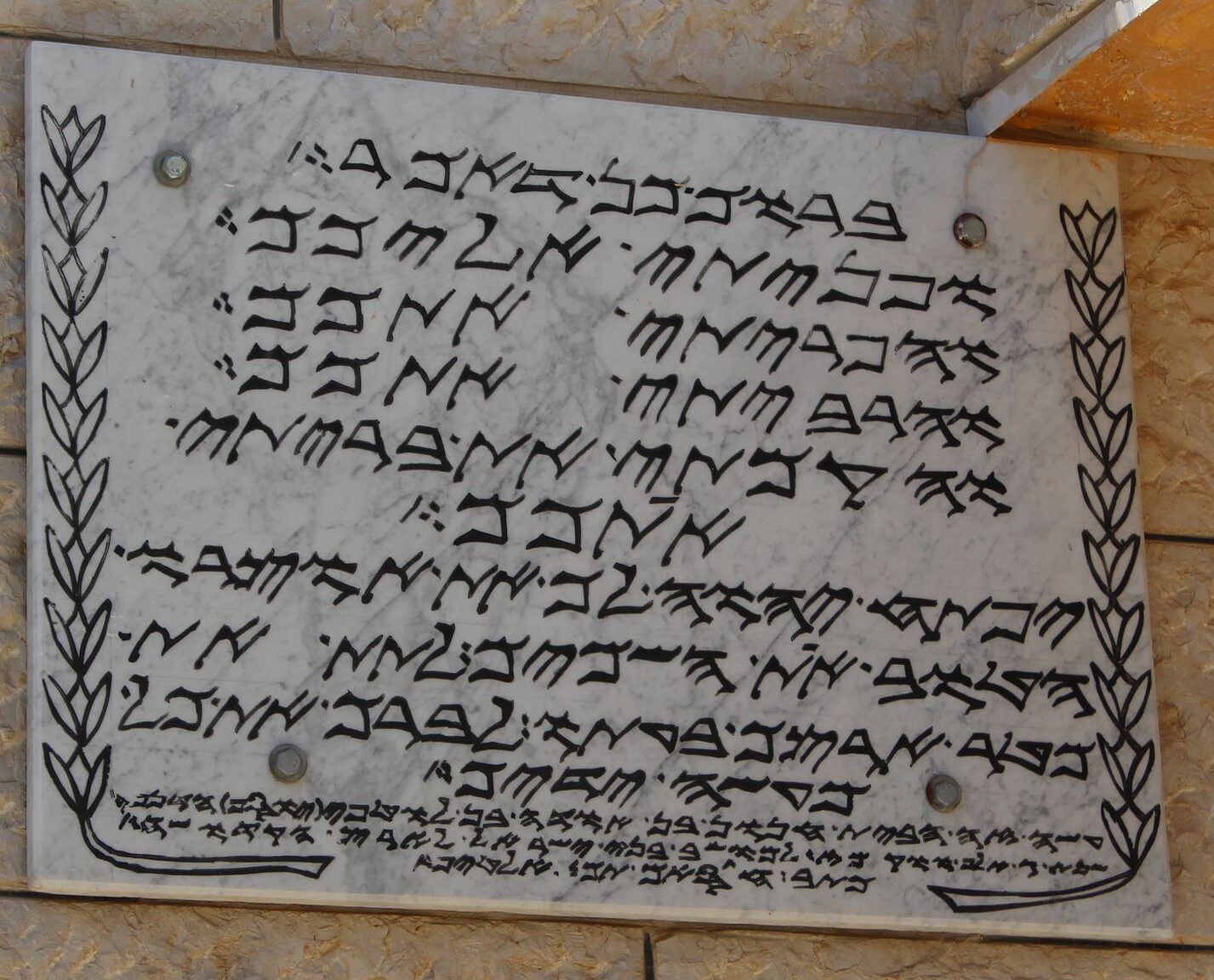

Dr. Stokes presented two examples of written texts that provide evidence of contact between Aramaic and Arabic. The first is a 4th century CE Arabic text from Namarah and Syria, written in Nabatean script, and the second is ʿEn ʿAvdat, from 1-2 centuries CE. The content suggested to the presenters that residents spoke Arabic while Aramaic was the primary written language. The spoken language influenced writing, creeping into quotes, poems, rhymes, greetings, and salutations.

With only scattered textual evidence, it has been difficult to determine what sort of linguistic interference was happening between Aramaic and Arabic. Some methodological questions about the potential substrates have to do with direction and similarities: “How can we determine if a feature has shifted from Aramaic to Arabic? Did a particular feature exist in Aramaic before the rise of Arabic? Is the feature similar/identical to the Arabic one, coincidentally?” and “In which dialect or period is the feature attested?”

One example of a root similarity is in the word sirwāl/širwāl, meaning “pants”. It is a common word, determined to have been used by Aramaic-speaking peoples and then attested in Arabic. However, the term also appears to have been common in texts featuring Greek, Latin, and Turkish languages. It seems that a word so commonly used in trade spreads widely and becomes common to many different languages. The point is that it is difficult to lock down the source of such a word.

Substrate influence is not simply a case of borrowed vocabulary, but it represents an awareness of semantic fields or variety and contact between those fields. The purpose of this study was to focus on features of Aramaic to Arabic linguistic influence. Some features of Western Aramaic that the presenters explored include pharyngeal weakening and conditioned affrication of stops.

For example, considering phonology, the presenters attributed a vowel shift to a conditioned linguistic response. To be specific, the presenters found a possible the ā > ō shift due to Aramaic influence—Qalamun rōs ~ Damascus rās “head”). Drs. Pat-El and Stokes tested this shift by examining its occurrence in Syriac, Eastern Texts, Bohtan (Neo-Aramaic), Turoyo (Central Neo-Aramaic), and Western Neo-Aramaic. They found that in the Eastern regions, there was no shift; in the Central regions, the shift depended on the syllable location; and in the Western regions, the shift depended on the structure and stress of the syllables. Thus, they concluded that this shift is not an example of an Aramaic substrate.

They also looked at syntax. The example they summarized was the syntactical placement of the direct object. In this observation, they found substantial evidence of a structure in the Aramaic writing influenced by Arabic spoken language tradition.

Dr. Stokes acknowledged the limits of such study, which were primarily identified as a lack of evidence of Arabic dialects. They also shared their hesitancy about such a method. Trying to determine how one language is influenced by or influences another is a tricky endeavor. This study showed just how difficult such a task might be.

Anyone who works with ancient languages has to deal with lexical issues. The nature of language is such that both realms of written and spoken versions influence and are influenced by the user(s) of the language. It can be difficult to avoid conflating complex issues of contact between languages. This especially becomes important when tracing language to make a point about history or theology.

One thing I appreciated about this presentation was the careful delimitation of possibilities. This study demonstrated the importance of humility in approaching the subject of contact between languages in a particular time and setting.

About this event

ANELC is a joint King’s College London–UCL series. This is the first year it is running as an online eLecture series. Read about #ANELC presentations. Also, read about other academic conferences.

Dr. Erica Mongé-Greer, holding a PhD in Divinity from the University of Aberdeen, is a distinguished researcher and educator specializing in Biblical Ethics, Mythopoeia, and Resistance Theory. Her work focuses on justice in ancient religious texts, notably reinterpreting Psalm 82’s ethics in the Hebrew Bible, with her findings currently under peer review.

In addition to her academic research, Dr. Mongé-Greer is an experienced University instructor, having taught various biblical studies courses. Her teaching philosophy integrates theoretical discussions with practical insights, promoting an inclusive and dynamic learning environment.

Her ongoing projects include a book on religious themes in the series Battlestar Galactica and further research in biblical ethics, showcasing her dedication to interdisciplinary studies that blend religion with contemporary issues.